Also called amalgamations, mergers, or consolidations, unit combinations are when multiple dwelling units are combined into one.

The conversion of a duplex into a single-family home is one common example.

Unit combinations typically occur because a property owner desires more interior space. They are largely unregulated in the United States, except for California and one small neighborhood in Chicago. In New York, unit combinations have resulted in the loss of 105,000 housing units since 1950. Outside of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Chicago, the trend has largely been ignored by urban planners.

The phenomenon raises important questions about housing supply as a focus of addressing the housing crisis. If planners are so intent upon allowing for more housing units through zoning reform, then how has this practice of unit elimination gone unexamined for so long?

Adaptive reuse, gone wrong?

Outside of planning regulation, the mergers raise questions of urban authenticity, historic district regulation, legacies of domesticity, and the ways in which cultural heritage is symbolized by the preservation of the built environment.

Genius loci: Intangible aspects of the built environment

Architectural conversions that reduce the number of units in the ‘everyday’ neighborhoods of yore deserve closer scrutiny through the lens of both theory and practice. Heritage scholarship, for one, recognizes the concept of cultural inheritance in the context of adaptive reuse projects. Lanz and Pendlebury write that adaptive reuse can result in a “a rift between the container and the content,” and ask: “Where does the identity and the memory of a building lie? Is it only in its exterior form and style or is it in its lived interiors?” (Lanz and Pendlebury, 2022, p. 456).

Despite this, aesthetic guidelines are largely superficial; literally of or belonging to the surface. Beyond protecting the bricks and sticks, cultural heritage may include lifeways, domestic legacies, and patterns of dwelling in space. This sentiment evokes the ancient Roman idea of genius loci, described by heritage planner Ron von Oers as the “complex laying of natural, cultural, built, intangible and local heritage, superimposed on and interacting with each other” (van Oers, 2015, p. 565). In the multi-family architecture of historic districts, for example, many structures have two doors to the street. Originally, these doors and stoops allowed for social interaction between neighbors. People entered their homes from the sidewalk. Today, in German Village and many historic districts like it, those entrances are entirely decommissioned and instead, rear garages and side doors serve as entryways. This relocation of access reduces the potential for social interaction and effectively suburbanizes the urban built environment.

While it is up to property owners to make these decisions, historic district regulations and oversight boards can enforce guidelines around matters of fenestration. The actions of individual property owners, after all, have a lasting impact on the built environment—beyond that of their tenure as a property owner. Acclaimed theorist Christian Norberg-Schulz argues that without genius loci, “the place loses its identity” and contends that architectural modifications are not neutral: “it makes sense to talk about ‘good’ and ‘bad’ changes” (Norberg-Schulz, pp. 180-182). That a ‘genius loci’ exists, however, is not necessarily obvious. Buildings, after all, are inanimate; they lack the animus that accompanies life.

“Genius of place may,” writes landscape historian John Dixon Hunt, “…not exist in itself, especially for a determined rationalist or ontologist” (Hunt, 2022, p. 38). Given the pragmatic tradition of planning theory, an investigation into how policy respects or neglects an abstract notion deepens both the theory and practice of adaptive reuse (Healey, 2009).

‘The houses of lesser people,’ now combined to house fewer people

More than purely architectural, genius loci is a multi-dimensional concept that challenges practitioners to consider the meanings, intents, and lived experiences embodied within the built environment. Those modest vernacular urban neighborhoods, written about by landscape theorists J.B. Jackson and Grady Clay using terms like “everyday America” and “epitome districts” (Clay, 1991; Jackson, 1984), are now special exceptions to suburban hegemony (Flint, 2006, p. 35; Teaford, 2020, p. vii).

Distinguished historian and architect Bernard Rudofsky also highlighted the importance of these landscapes—calling them “the houses of lesser people” (Rudofsky, 1964, p. 2).

While it is often “gingerbread mansions of tourist-brochure lore” which receive the most attention, urban planner Max Podemski channels Rudofsky when he writes that it is actually the “common everyday houses that represent our nation’s most enduring architectural achievement” (Podemski, 2024, p. 7). The practice of dwelling unit combinations, then, could be construed as a threat to these common, everyday houses by transforming them from working class artifacts into real estate showcases.

Examples of conversions/combinations

German Village Historic District

Columbus, Ohio

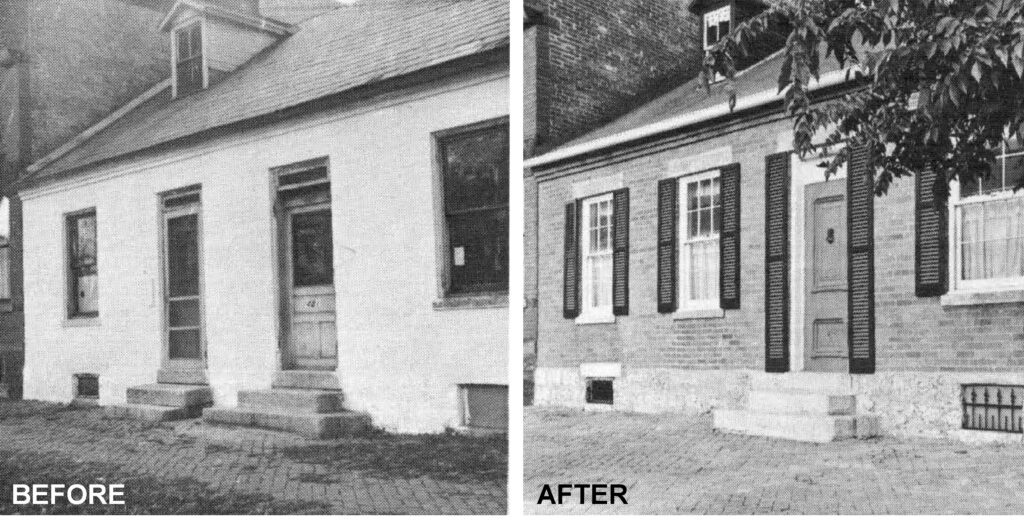

Formerly a duplex, now a single-family dwelling

Formerly a duplex, now a single-family dwelling

Formerly multiple structures, now one single-family dwelling of 7,265 sq. ft.

Formerly a duplex, now a single-family dwelling

Formerly a duplex, now a single-family dwelling of 2,409 sq. ft.

Formerly a duplex, now a single-family dwelling of 2,539 sq. ft.

Formerly a duplex, now a single-family dwelling

Formerly a duplex, now a single-family dwelling

Formerly two single-family dwellings, now one dwelling of more than 6,000 sq. ft.

Additional examples

New Orleans

Richmond

St. Louis